Machine learning deserves its own flavor of Continuous Delivery

Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning, in practice.

Things feel slightly different - but eerily similar - when traveling through Canada as an American. The red vertical lines on McDonald’s straws are a bit thicker, for example. It’s a lot like my travels through the world of data science as a software engineer.

While the data science world is magical, I’m homesick for the refined state of Continuous Delivery (CD) in classical software projects when I’m there. What’s Continuous Delivery?

Martin Fowler says you’re doing Continuous Delivery when:

- Your software is deployable throughout its lifecycle

- Your team prioritizes keeping the software deployable over working on new features

- Anybody can get fast, automated feedback on the production readiness of their systems any time somebody makes a change to them

- You can perform push-button deployments of any version of the software to any environment on demand

For a smaller-scale software project deployed to Heroku, Continuous Delivery (and its hyper-active sibling Continuous Deployment) is a picture of effortless grace. You can setup up CI in minutes, which means your unit tests run on every push to your git repo. You get Review Apps to preview the app from a GitHub pull request. Finally, every git push to master automatically deploys your app. All of this takes less than an hour to configure.

Now, why doesn’t this same process work for our tangled balls of yarn wrapped around a single predict function? Well, the world of data science is not easy to understand until you are deep in its inner provinces. Let’s see why we need CD4ML and how you can go about implementing this in your machine learning project today.

Why classical CD doesn’t work for machine learning

I see 6 key differences in a machine learning project that make it difficult to apply classical software CD systems:

1. Machine Learning projects have multiple deliverables

Unlike a classical software project that solely exists to deliver an application, a machine learning project has multiple deliverables:

- ML Models - trained and serialized models with evaluation metrics for each.

- A web service - an application that serves model inference results via an HTTP API.

- Reports - generated analysis results (often from notebooks) that summarize key findings. These can be static or interactive using a tool like Streamlit.

Having multiple deliverables - each with different build processes and final presentations - is more complicated than compiling a single application. Because each of these is tightly coupled to each other - and to the data - it doesn’t make sense to create a separate project for each.

2. Notebooks are hard to review

Code reviews on git branches are so common, they are baked right into GitHub and other hosted version control systems. GitHub’s code review system is great for *.py files, but it’s terrible for viewing changes to JSON-formatted files. Unfortunately, that’s how notebook files (*.ipynb) are stored. This is especially painful because notebooks - not abstracting logic to *.py files - is the starting point for almost all data science projects.

3. Testing isn’t simply pass/fail

Elle O'Brien covers the ambigous nature of using CI for model evaluation.

It’s easy to indicate if a classical software git branch is OK to merge by running a unit test suite against the code branch. These tests contain simple true/false assertions (ex: “can a user signup?”). Model evaluation is harder and often requires a data scientist to manually review as evaluation metrics often change in different directions. This phase can feel more like a code review in a classical software project.

4. Experiments versus git branches

Software engineers in classical projects create small, focused git branches when working on a bug or enhancement. While branches are lightweight, they are different than model training experiments as they usually end up being deployed. Model experiments? Like fish eggs, the vast majority of them will never see open waters. Additionally, an experiment likely has very few changes code changes (ex: adjusting a hyper-parameter) compared to a classical software git branch.

5. Extremely large files

Most web applications do not store large files in their git repositories. Most data science projects do. Data almost always requires this. Models may require this as well (there’s also little point in keeping binary files in git).

6. Reproducible outputs

It’s easy for any developer on a classical software project to reproduce the state of the app from any point in time. The app typically changes in just two dimensions - the code and the structure of the database. It’s hard to get to a reproducible state in ML projects because many dimensions can change (the amount of data, the data schema, feature extraction, and model selection).

How might a simple CD system look for Machine Learning?

Some of the tools available to make CD4ML come to life.

In the excellent Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning, the Thoughtworks team provides a sample ML application that illustrates a CD4ML implementation. Getting this to run involves a number of moving parts: GoCD, Kubernetes, DVC, Google Storage, MLFlow, Docker, and the EFK stack (ElasticSearch, FluentD, and Kibana). Assembling these ten pieces is approachable for the enterprise clients of Throughworks, but it’s a mouthful for smaller organizations. How can leaner organizations implement CD4ML?

Below are my suggestions, ordered by what I’d do first. The earlier items are more approachable. The later items build on the foundation, adding in more automation at the right time.

1. Start with Cookiecutter Data Science

Nobody sits around before creating a new Rails project to figure out where they want to put their views; they just run rails new to get a standard project skeleton like everybody else.

When I view the source code for an existing Ruby on Rails app, I can easily navigate around as they all follow the same structure. Unfortunately, most data science projects don’t use a shared project skeleton. However, it doesn’t have to be that way: start your data science project with Cookiecutter Data Science rather than dreaming up your own unique structure.

Cookiecutter Data Science sets up a project structure that works for most projects, creating directories like data, models, notebooks, and src (for shared source code).

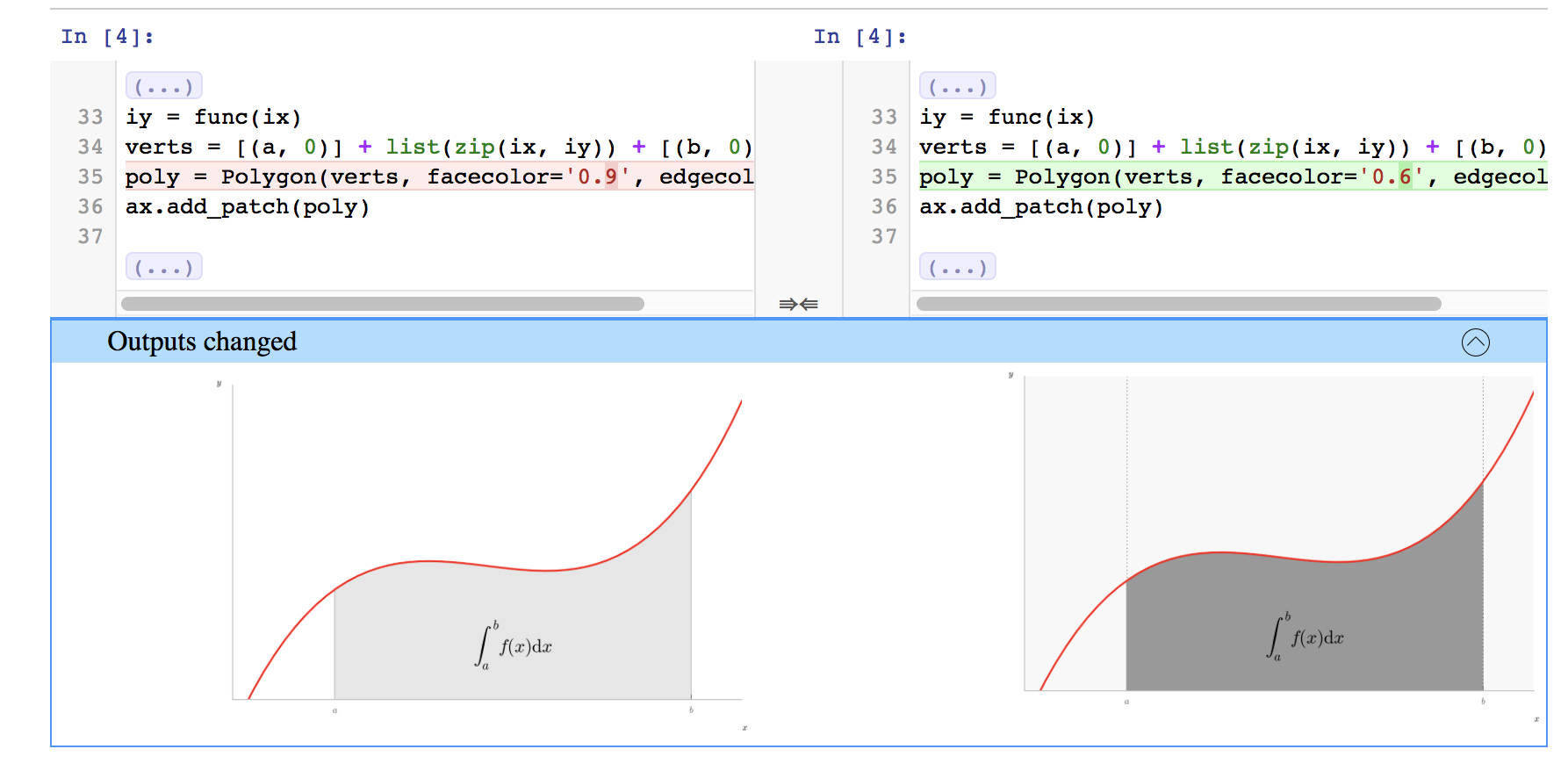

2. nbdime or ReviewNB for better notebook code reviews

nbdime is a Python package that makes it easier to view changes in notebook files.

It’s hard to view changes to *.ipynb in standard diff tools. It’s trivial to conduct a code review of a *.py script, but almost impossible with a JSON-formatted notebook. nbdime and ReviewNB make this process easier.

3. dvc for data files

dvc add data/ git commit -ma "Storing data dir in DVC" git push dvc push

After installing dvc and adding a remote, the above is all that's required to version-control your data/ directory with dvc.

It’s easy to commit large files (esc. data files) to a git repo. Git doesn’t handle large files well: it slows things down, can cause the repo to grow in size quickly, and you can’t really view diffs of these files anyway. A solution gaining a lot of steam for version control of large files is Data Version Control (dvc). dvc is easy to install (just use pip) and its command structure mimics git.

But wait - you’re querying data direct from your data warehouse and don’t have large data files? This is bad as it virtually guarantees your ML project is not reproducible: the amount of data and schema is almost guaranteed to change over time. Instead, dump those query results to CSV files. Storage is cheap, and dvc makes it easy to handle these large files.

4. dvc for reproducible training pipelines

dvc isn’t just for large files. As Christopher Samiullah says in First Impressions of Data Science Version Control (DVC):

Pipelines are where DVC really starts to distinguish itself from other version control tools that can handle large data files. DVC pipelines are effectively version controlled steps in a typical machine learning workflow (e.g. data loading, cleaning, feature engineering, training etc.), with expected dependencies and outputs.

You can use dvc run to create a Pipeline stage that encompasses your training pipeline:

dvc run -f train.dvc \

-d src/train.py -d data/ \

-o model.pkl \

python src/train.py data/ model.pkl

dvc run names this stage train, depends on train.py and the data/ directory, and outputs a model.pkl model.

Later, you run this pipeline with just:

dvc repro train.dvc

Here’s where “reproducible” comes in:

- If the dependencies are unchanged -

dvc reposimply grabsmodel.pklfrom remote storage. There is no need to run the entire training pipeline again. - If the dependencies change -

dvc repowill warn us and re-run this step.

If you want to go back to a prior state (say you have a v1.0 git tag):

git checkout v1.0 dvc checkout

Running dvc checkout will restore the data/ directory and model.pkl to is previous state.

5. Move slow training pipelines to a CI cluster

In Reimagining DevOps, Elle O’Brien makes an elegant case for using CI to run model training. I think this is brilliant - CI is already used to run a classical software test suite in the cloud. Why not use the larger resources available to you in the cloud to do the same for your model training pipelines? In short, push up a branch with your desired experiment changes and let CI do the training and report results.

Christopher Samiullah also covers moving training to CI, even providing a link to a GitHub PR that uses dvc repo train.dvc in his CI flow.

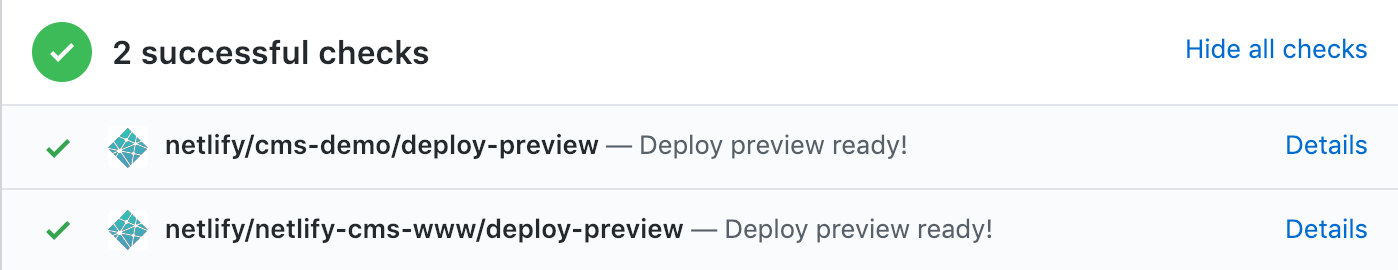

6. Deliverable-specific review apps

Netlify, a PaaS for static sites, lets you view the current version of your site right from a GitHub pull request.

Platforms like Heroku and Netlify allow you to view a running version of your application right from a GitHub pull request. This is fantastic for validating things are working as desired. These are great for presenting work to non-technical team members.

Do the same using GitHub actions that start Docker containers to serve your deliverables. I’d spin up the web service and any dynamic versions of reports (like something built with Streamlit).

Conclusion

Like eating healthy, brushing your teeth, and getting fresh air, there’s no downside to implementing Continuous Delivery in a software project. We can’t copy and paste the classical software CD process on top of machine learning projects because an ML project ties together large datasets, a slow training process that doesn’t generate clear pass/fail acceptance tests, and contains multiple types of deliverables. By comparison, a classical software project contains just code and has a single deliverable (an application).

Thankfully, it’s possible to create a Machine Learning-specific flavor of Continuous Delivery (CD4ML) for non-enterprise organizations with existing tools (git, Cookiecutter Data Science, nbdime, dvc, and a CI server) today.

CD4ML in action? I’d love to put an example machine learning project that implements a lean CD4ML stack on GitHub, but I perform better in front of an audience. If I get enough subscribers below, I’ll put this together. Please subscribe!

Elsewhere

- Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning - this blog post (and the CD4ML acronym) wouldn’t exist without the original work of Daniel Sato, Arif Wider, and Christoph Windheuser.

- First Impressions of Data Science Version Control (DVC) - this is a great technical walkthrough migrating an existing ML project to using DVC for tracking data, creating pipelines, versioning, and CI.

- Reimagining DevOps for ML by Elle O’Brien - a concise 8 minute YouTube talk that outlines a novel approach for using CI to train and record metrics for model training experiments.

- How to use Jupyter Notebooks in 2020 - a comprehensive three-part series on architecting data science projects, best practices, and how the tools ecosystem fits together.